A-Arms, Roll Center, Camber Gain, and How to Improve Them

Suspension geometry is one of the most misunderstood and most important parts of how a GM vehicle handles. Horsepower gets the headlines, but geometry is what determines whether a car feels planted and confident or unpredictable. Concepts like roll center, and camber gain aren’t abstract engineering terms, they are directly responsible for tire contact, stability, and driver feedback.

What Suspension Geometry Actually Does

At its core, suspension geometry controls:

-

How the tire contacts the road during movement

-

How the vehicle reacts to cornering, braking, and acceleration

-

How body roll is managed

-

How predictable the car feels at the limit

Bad geometry forces the tire to work at poor angles. Good geometry keeps the tire flat, loaded evenly, and consistent through suspension travel.

A-Arms (Control Arms): The Foundation

Most GM front suspensions, especially classic cars and trucks, use double A-arm (double wishbone) designs.

How A-Arms Work

-

Upper and lower control arms locate the spindle

-

Their length, angle, and mounting points determine camber curve and roll center

-

The relationship between upper and lower arms controls how the tire moves during compression

GM Reality (Especially Older Cars)

Many factory GM suspensions in the 1960’s weren’t designed around performance. Plus we have learned a lot about the suspension geometry since the 60’s as well.

The original suspension was designed for:

-

Ride comfort

-

Narrow bias-ply tires

-

Low cornering loads

Once you add modern radial tires, wider wheels, or aggressive driving, the stock geometry quickly shows its age.

Camber Gain: Why It Matters

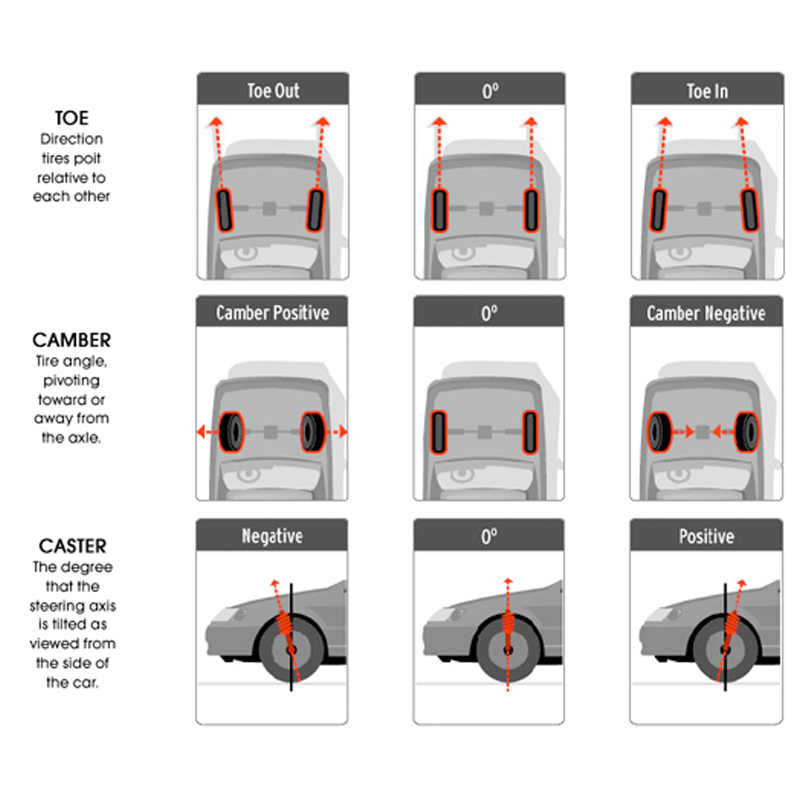

Camber is the inward or outward tilt of the tire.

-

Negative camber (top of tire inward) improves cornering grip

-

Positive camber hurts grip

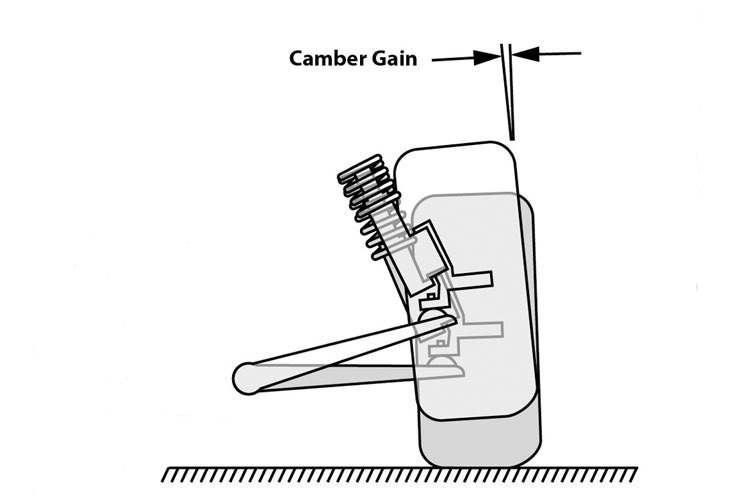

Camber Gain Explained

Camber gain is how much negative camber the suspension adds as it compresses in a corner. As the body rolls, the suspension should add negative camber to keep the tire flat on the road. More tire on the ground means more traction and faster, more confident cornering. Unfortunately a lot of the factory GM suspension in the 60’s and 70’s would give you positive camber gain, making handling even worse!

Why This Is a Problem

-

Reduced cornering grip

-

Excessive outer tire wear

-

Car feels unstable when pushed

Fixes

-

Taller upper ball joints

-

Revised upper control arm angles

-

Aftermarket arms designed to increase camber gain

-

Drop spindles (when properly engineered)

Roll Center: The Invisible Pivot Point

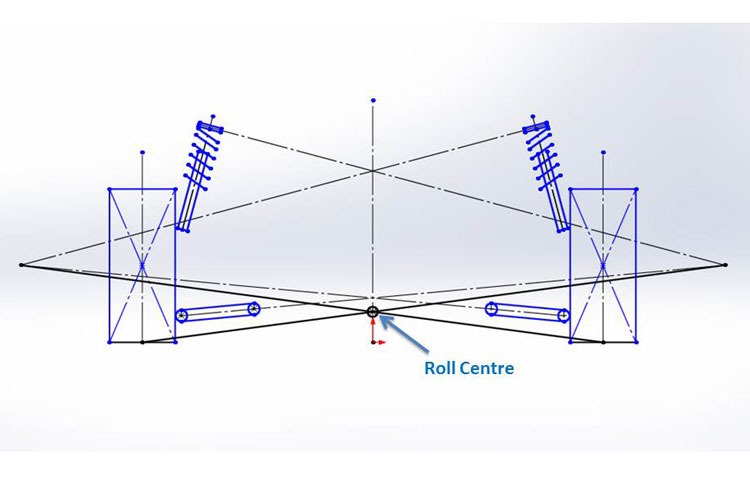

The roll center is an imaginary point around which the vehicle’s body rolls during cornering.

Why Roll Center Is Critical

-

Determines how much the body rolls

-

Affects weight transfer speed

-

Influences steering feel and stability

GM Factory Roll Center Issues

On many classic GM platforms:

-

Roll centers are too low

-

Excessive body roll occurs

-

Weight transfer becomes slow and uncontrolled

Lowering the car without correcting geometry often makes this worse.

Ideal Roll Center Behavior

-

Front and rear roll centers should work together

-

Roll center should stay reasonably consistent through travel

-

Excessive roll should be controlled by geometry—not just stiff springs

Common GM Suspension Styles (Pros & Cons)

1. Double A-Arm (Short/Long Arm – SLA)

Used on: Classic Chevelles, Camaros, Tri-Five Chevys, C10s, many performance GM cars

Pros

-

Excellent camber control when designed correctly

-

Highly tunable

-

Best performance potential

Cons

-

Factory geometry often outdated

-

Sensitive to ride height changes

-

Requires proper upgrades to shine

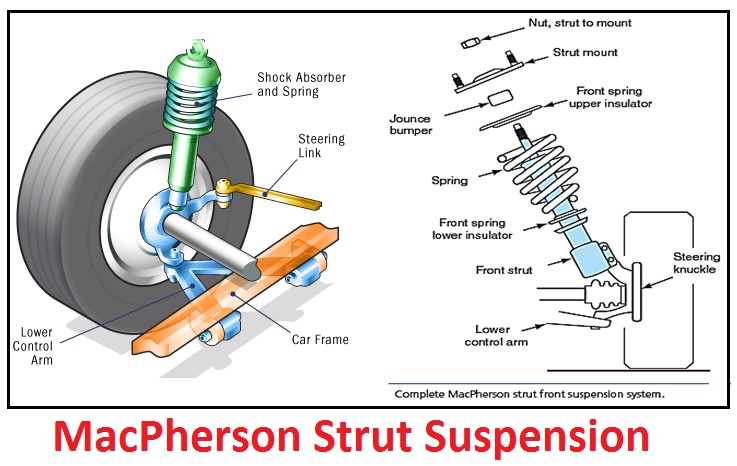

2. MacPherson Strut

Used on: Many modern GM cars (F-body, Alpha platform, etc.)

Pros

-

Lightweight

-

Simple

-

Efficient packaging

Cons

-

Limited camber gain

-

Less adjustability

-

Geometry changes dramatically when lowered

3. Solid Axle (Leaf Spring or 4-Link)

Used on: Classic GM trucks, muscle cars, older performance platforms

Pros

-

Strong

-

Simple

-

Predictable in straight-line use

Cons

-

Limited camber control (rear axle)

-

Roll center fixed by design

-

Needs good front suspension to compensate

How Geometry Gets Ruined (Common Mistakes)

-

Lowering springs without correcting control arm angles

-

Wide wheels with incorrect offset

-

Drop spindles with poor steering arm geometry

-

Mixing random suspension parts without a plan

-

Relying on stiff springs instead of geometry

Good suspension isn’t about stiffness, it’s about control. Stiffening up the suspension is masking the issues.

How to Improve GM Suspension Geometry (The Right Way)

1. Correct Control Arm Angles

-

Revised upper arm geometry

-

Taller ball joints

-

Proper instant center placement

2. Improve Camber Curve

-

Aftermarket upper control arms

-

Correct spindle height

-

Alignment specs matched to tire size and use

3. Fix Roll Center Height

-

Geometry-correct drop spindles

-

Optimized control arm pivot locations

-

Balanced front/rear roll centers

4. Don’t Ignore the Rear

-

Rear suspension affects front grip

-

Proper rear roll center improves balance

-

Sway bar tuning matters

Alignment: Where Geometry Becomes Real

You can go out and buy the most expensive suspension and slap it on, but without a proper alignment it’s not going to do anything. The caster, camber, along with toe-in and toe-out has to be adjusted and dialed in to feel the rewards of your hard work.

Typical performance-oriented GM alignment goals:

-

Increased negative camber

-

More positive caster

-

Slight toe-in for stability

Alignment should match:

-

Tire width

-

Intended use (street, autocross, track)

-

Suspension design

If you’re wanting your classic GM car to handle better, hop on SS396.com for a full line up of parts to make that happen – or call (203) 235-1200!